- Home

- Ricardas Gavelis

Vilnius Poker Page 8

Vilnius Poker Read online

Page 8

Why doesn’t a single theory answer these simple questions? Why do all the great philosophical systems, all the Hegels and Kants together, fail to explain these basic things? Why?

Maybe that’s the way, and just that way, that man unavoidably is? Maybe all of these horrifying things aren’t the province of theory, but rather axioms that you’ll neither prove nor disprove? Maybe a soulless doom is programmed into all of us from the start? Every nation has the kind of government it deserves, and so on?

I cannot bear assumptions like that, assumptions that acrimoniously belittle people. I can’t bear them! But an investigator must be calm and objective, he must rely only on facts.

Children deny those revolting assumptions. The very existence of children. A foolish boy who tries to boss the neighborhood kids around will be ridiculed immediately. There is no silent gray majority in the world of children. You could arrest a thousand, a million children, but as long as at least one remains alive and free, there will be a child’s view of justice in the world, there will be someone to shout that the king is naked. An unspoiled child tries to be more like the stronger or smarter ones, not to pull them down. No, no, a human isn’t born a kanukas!

The ruination takes over later, when children are taught to rat on others, when they learn it’s not worth ridiculing the kid with pretensions to be a little king, since he’s the boss’s son. When someone convinces them (convinces without presenting any arguments) that it’s imperative to participate in the idiotic play of life, even knowing it’s idiotic. Convinces them there is no choice—either float in the ship of fools, or drown.

How can you explain all of this, supposing They don’t exist?

ERGO: THEY EXIST.

Thank God, even Their system isn’t omnipotent. Not everyone gives in to being kanuked. Some people have an incomprehensible metaphysical power (frequently not even suspecting it themselves) to elude the thickest of Their nets. Alas, there’s very few of them, terribly, tragically, few.

At that time I hadn’t comprehended Their abnormal logic (Their patho-logic). I didn’t know even a hundredth part of their methods, but I had already started to grasp what sort of threat hung over all of us. Gedis was the first victim to die in my presence. To this day I’m not sure he knew about Them. Without a doubt, Gediminas was better, smarter, more energetic than I am. Unfortunately, it’s by no means a given that every good and intelligent person will come across Their system. You must experience a great deal of evil in your life, real evil; you must thoroughly scrutinize its pupil-less eyes. Besides, you must have a seed of real evil in yourself. It’s awful, but that’s the way it is: if you don’t have evil within yourself, you won’t be able to recognize and comprehend the evil in the world. So I cannot be sure that Gedis knew. He was only the first victim I recognized—who can count how many of them I had seen just in the Stalinist camps, without even suspecting they were Their victims. I have no doubts about the reasons for Gedis’s death. I hastened to find regularities of a more general nature. I searched gropingly: I tried to remember all mathematicians, all musicians, all car crashes. At last, I turned up a significant car crash in my memory. I remembered how Albert Camus died. That was how my research moved into a completely new sphere.

The entire story of Camus’s life always seemed somewhat strange to me. Hidden in the sands of Algeria, he could, of course, come across more essential things than the inhabitants of large metropolitan centers can. In a center of culture and science, in the hum of people, They feel safe; They blend into the throng, into the profusion of words and opinions. They always dictate intellectual fashions, by this method concealing things that are troublesome to Them. Inhabitants of obscure places have far more time to delve into the essence of the world, but also far fewer chances for their ideas to reach humanity. Camus successfully reconciled the qualities of a hermit and Europe’s darling.

His spiritual activity was twofold. Some of his writings, let’s say, The Myth of Sisyphus, seem to indicate that Camus was practically an apologist for Their activities. This is confirmed in part by his Nobel Prize (almost always it’s Their emissaries who determine the awarding of official prizes: I emphasize—neither Joyce, nor Kafka, nor Genet received any prizes).

On the other hand, The Plague or The Stranger brazenly intrude into Their inviolable domain. The portrayal of the plague is strongly reminiscent of an allegory of Their system, while Meursault is one of the most influential portraits of a kanuked being. There’s no sense delving into Camus’s actual activities—the most significant things won’t be found in the tangle of his biography. But his death is worth pondering. Perhaps at first Camus was an obedient (let’s say an inadvertent) servant of Theirs, and later he saw through things. Maybe he was cleverly feigning all the time, secretly damaging Them. We can only speculate. One way or another, he slowly began behaving in an unacceptable manner; maybe he even did things to Them that we are forbidden to talk about (even to think about them is dangerous). Retribution was quick. The fatalistic death, the lost manuscripts—all of that’s in an all-too-familiar style. Gediminas’s letters also disappeared without a trace.

Camus’s precedent was the first I wrote into the great list of Their victims.

The fact that you won’t find straightforward information about Them in books ultimately proves They exist. It would be easy to fight with a concrete societal or political organization that everyone knows or has at least come across. An identified enemy is almost a conquered enemy. Everyone would have risen up against Them a long time ago; They would have been destroyed at some point. Unfortunately, Their race exists and works harmoniously. This proves that they’re hidden, undiscovered, uninvestigated. But whether They want to or not, they leave traces behind. All of Their victims are indelible footprints. Let’s take the story of Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate. Anyone who’s seen Polanski’s films will understand that he should have shut his trap (or more precisely—broken his film camera). Both his vampires and Rosemary’s Baby slowly, but unavoidably, lead to Their lair. True, Satan Manson (his leaders!) miscalculated something, Polanski was left unharmed, his wife died (or maybe that was just exactly Their patho-logical plan). However, the time will come yet when some barb-eyed Circe of the Hollywood villas will do him in. It’s silly to talk about a shortage of footprints. There are plenty of prints—it’s even horrifying how many there are, those most often bloody footprints of Theirs.

Sometimes it’s almost suspicious how far individual researchers manage to get. I’m not even talking about Kafka. There’s another one who particularly astounded me. He’s from Buenos Aires, by the name of Ernesto Sabato. I was simply horrified when I read his book. I couldn’t believe my eyes: Sabato openly described some of Their methods—although it’s true, he didn’t mention anything at all about Their goals. In addition, he persistently associated them with the powers of hell. That aroused my suspicions. Strangest of all, he wrote about the blind, and they, after all, don’t have a gaze. At first I just couldn’t understand this inversion. It sufficed to scrutinize two words—AKLAS and AKYLAS: AK(Y)LAS, the words for blind and sharp-sighted. Perhaps the particularly archaic Lithuanian language has preserved even more secret connections, connections which They have managed to eliminate from other languages?

However, this discovery didn’t solve the problem of Ernesto Sabato, and it didn’t dispel my suspicions. It wasn’t plausible that an Argentinean would know Lithuanian. Unfortunately, I’ll never travel to Argentina, I’ll never speak to him nor track him down. However, his picture fell into my hands in the nick of time.

A man with a pudgy little face and small eyes looked out of the photograph, a man who looked sufficiently satisfied with himself. Not at all like a man condemned to death, a man who knows the secrets of The Way. Besides, he’s too well-known, at least in Argentina. Argentina—where a good number of Hitler’s toadies hid! All of these facts opened my eyes. Sabato’s book is merely a clever attempt to turn the search in an erroneous direction. They set quite a few tr

aps like that. I was saved by my native language and vigilance. They didn’t succeed in fooling me.

I don’t know why it’s the Lithuanian language in particular. I don’t know why it’s in Lithuania in particular that They so openly show themselves, or disguise themselves so poorly. I don’t know why it’s Vilnius in particular that’s so important. All of that is still a mystery to me.

They overshot, if they think that I’ll study only the books in my own library. I’ve spent quite a bit of time in the University’s manuscript sections. There I came across a manuscript, a transcript of a pre-war dissertation, that shocked me.

During the time of Zygimantas Augustus (the second half of the 16th century), a Basilisk appeared in Vilnius that killed people with its gaze. It was the horrible metamorphosis of a bird; it killed people with the power of its eyes, or sometimes with a deep breath. It hid in the mysterious Didžiosios Street district and had been discovered, but later disappeared. It was possible to temporarily defend yourself from its powers with dry tree leaves—they absorbed the strength of its gaze.

In the dissertation, this unique information was described as if merely in passing, as one of many legends of Vilnius—with the author’s (a woman’s!) perfectly understandable caution. After I read this, I didn’t sleep for several nights. I frantically looked for information about the Vilnius Basilisk—unfortunately, in vain.

Yet one more very important observation: students at Vilnius University used to organize ceremonies celebrating victory over the Basilisk, but later they were forbidden and forgotten.

How much more invaluable information from the past is still hidden in manuscripts!

She talks and talks; she’s been quiet for too long. Even now she’s silent the entire workday and doesn’t even glance at me, while I fume, irritated by blond-fluffed Stefa buzzing around me. At one time I used her in some of my inquiries. Lolita avoids her; she avoids them all, but after work, left alone with me, she bursts out. We spend entire evenings walking around Vilnius; I haven’t roamed through the city this much in a long time. Lola constantly scatters words, sentences, and difficult tirades about. In the narrow little streets, in the grim gateways, next to the old houses, the words she’s spoken pile up in heaps. They are distinctive: smaller or larger, arranged tidily or thrown about any which way. They pretend to be rocks, tree leaves swept together, or even trash.

She talks incessantly.

“Vytas,” is how it most often starts, “Vytas, do you want me to tell you about . . .”

A typical woman’s question. How can I say what I want? But the worst of it is that I do enjoy it when she talks. I enjoy listening to her like music. She improvises as she speaks, returning to the same place (in the story and in the city) a hundred times, or turning in circles, or wandering aimlessly. She starts to talk about her village, about her grandparents, and I know we’ll shortly turn up in Gediminas Square. Mentioning her husband, we’re surely cutting across Vokiečių Street (now it’s Muziejaus). Her jazz of words and routes has become part of me; we’re not just walking through Vilnius, but through my internal streets too.

“I’m drawn to horrible people,” she says with inner fear. This is a favorite theme of hers (down Gedimino Boulevard, then to Tortorių Street, deeper and deeper into the bowels of Vilnius). “I’m fascinated by doomed men, the ones that smell of misfortune from a distance . . .”

Now she’s a bodiless, extinct, paralyzed fairy of Vilnius: a pale shadow on the dark background of a wall, a dark shadow on the background of a bright wall. The charms of Lola’s body have vanished somewhere. I don’t even notice her breasts or the mysterious roundness of her belly; I listen more than I look. I like Lolita’s voice. In it I hear the quiet rustle of an inner fire; the fire there isn’t extinguished yet. Her voice is multifaceted: you can hear her girlish dreams and her desires in it, her favorite music, even her breasts and her long legs wrapped in fluids of beauty.

Now I’m walking beside her; I see her lips, I even see the words themselves—it’s a shame they fall on the sidewalk and roll into the dark portals; they should be collected and saved.

“I’m persecuted by people who are marked with the sign of misfortune,” she repeats seriously. “It sounds silly: marked with the sign of misfortune, like in a Russian ballad . . . We no longer know how to say what we want to say, there are just strangers’ phrases in our heads . . . Although, no, I know: if everyone were to speak their own language, we’d never understand one another. But it would be so beautiful! . . . The sign of misfortune . . . I look for that kind of person myself, that’s the worst. The other kind don’t interest me . . . What is a man, Vytas?”

“A face and sexual organs. To distinguish them from others and to multiply!”

“Jesus and Mary,” she sighs, “You’re a silly, foul-mouthed person. A man is his eyes. Eyes are everything, even if you’re physically blind. And the invisible fiery brand on a person’s forehead.”

She suddenly stops. She frequently comes to a standstill this way, as if she had to hammer in a little stake here, to leave a sign. In just this spot. Here, where she spoke of eyes.

“And me?” I ask, because by now we have turned in the direction of the University and my turn to speak has come. “What’s written on my forehead? Or written on some other spot? What’s written there that’s so significant, that you fell for a dying old man? It isn’t by chance an Electra complex?”

“You’re a pig. And terribly spiteful,” she says, after a long, long silence (all the way to Stiklių Street). “You hate me. This always, always happens to me . . .”

Suddenly she stops on the very corner, and leans against the wall; her face looks up, straight at me. Now she has a body: and eyes, turned in towards herself, and breasts (they furiously press up against me), and the curves of the thighs hidden under her clothing, and her flat goddess’s belly. She suddenly comes to life, her eyes blaze and her fingers angrily pick at the wall.

“And if I were to start needling at you too? We’d go on picking on one another? You’d get mad first. Men are very touchy.”

I follow from behind, hanging back a bit, and wait patiently, because she speaks of intimate things only in Didžiosios Street. (Now she’s in Gorky Street. What a sad, sad absurdity—what does some Gorky, a miserable kanukized servant, have in common with Vilnius?) It’s only in this street, descending downwards, that she talks about what matters most to her. (Climbing up she always asks me about the camp.) It’s probably still quite early, but Vilnius is empty. Vilnius gets emptier by the day—the emptier it gets, the worse the crush in the streets. A dead city, and above it hangs a fog of submissive, disgusting fear. Vilnius, which I love, Vilnius, which is I myself, buried under lava like Pompeii, under the seas like Atlantis. Lolita and I are shadows: the live Vilniutians, that throng of ants, that murky river, don’t wander the evening streets, don’t talk the way we do.

“I can’t stand dead ideas,” she suddenly says. “I can’t stand symbols and metaphors . . . My mother was obsessed with the idea of innocence. The idea of consummate innocence. Do you know what innocence is?”

“This membrane in the vagina. Sometimes very difficult to tear.”

“Vytas, stop it,” she fumes. “You’re making fun of me. I won’t tell you anything . . . Although as it happens, it was exactly with a membrane that everything started . . .”

Agitated, she looks around as if she were searching for ears in the walls, then she cowers and whispers. Even her whisper plays its own music. She doesn’t hiss like others do; you’d think she was uttering secret curses—only genuine fairies know them.

“Whoever walks between these walls can’t be innocent. This damn city wouldn’t put up with innocence . . . But no, I was talking about the past, about my mother . . . At first my maidenly innocence really was what mattered most to her. You can’t imagine how much you can talk about that. How many days, evenings, nights. For years! Mother started when I was about six. I’d run around the yards, mostly with the boys

. For some reason I wasn’t attracted to dolls; I liked hideaways, ruins and boys better . . . She immediately started in giving me lectures about innocence. She wanted to explain what innocence is. Abstract innocence—that’s what mattered most to her. It was complete mysticism . . . Later she switched to concrete maidenly innocence, as a separate example. She explained in excruciating detail all the methods whereby, in her opinion, it was possible to lose your innocence. All night long—so I would know what I had to avoid. Her imagination was nightmarish. But enough of that . . . Of course, I didn’t understand anything, but an image of mystical innocence formed within me. A live innocence . . . Practically a little beast . . . It was so . . . sticky, without any holes or openings, hairy, and really cold—so you wouldn’t want to touch it. My six- or seven-year-old brain was full of that cold, hairy innocence, can you imagine? I’d dream of it. And how did everything turn out?”

She stops again, as if she needs to concentrate to answer, and takes a deep breath of air, Vilnius’s gray air. It smells of decay. Every evening street of Vilnius looks like a narrow path through an invisible bog. If you were to go a couple of steps to the side you’d immediately feel the sweetish breath of the swamp, the smell of peaceful decay.

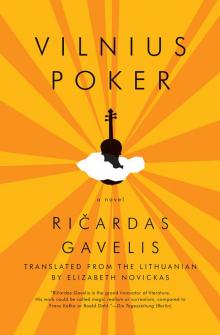

Vilnius Poker

Vilnius Poker