- Home

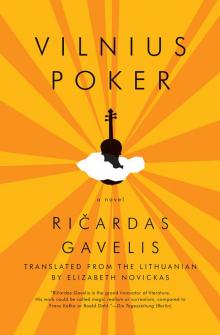

- Ricardas Gavelis

Vilnius Poker

Vilnius Poker Read online

Copyright

Copyright © Ričardas Gavelis, 1989

Translation copyright © Elizabeth Novickas, 2009

Originally published as Vilniaus pokeris by Vaga, 1989

First edition, 2009

First digital edition, 2013

All rights reserved

This work was published with support from Books from Lithuania, using funding from the Cultural Support Foundation of the Republic of Lithuania.

Gracious acknowledgments to Professor Violeta Kelertas for her assistance.

An excerpt of Vilnius Poker originally appeared in Two Lines #15.

ISBN-13: 978-1-934824-55-9

ISBN-10: 1-934824-55-0

Design by N. J. Furl

Open Letter is the University of Rochester’s nonprofit, literary translation press:

Lattimore Hall 411, Box 270082, Rochester, NY 14627

www.openletterbooks.org

PART ONE

THEY

Vytautas Vargalys. October 8, 197. . .

A narrow crack between two high-rises, a break in a wall encrusted with blind windows: a strange opening to another world; on the other side children and dogs scamper about, while on this side—only an empty street and tufts of dust chased by the wind. An elongated face, turned towards me: narrow lips, slightly hollowed cheeks, and quiet eyes (probably brown)—a woman’s face, milk and blood, questioning and torment, divinity and depravity, music and muteness. An old house entangled in wild grape vines in the depths of a garden; a bit to the left, dried-up apple trees, and on the right—yellow unraked leaves; they flutter in the air, even though the tiniest branches of the bushes don’t so much as quiver . . .

That was how I awoke this morning (some morning). Every day of mine begins with an excruciatingly clear pictorial frontispiece; you cannot invent it or select it yourself. It’s selected by someone else; it resonates in the silence, pierces the still sleeping brain, and disappears again. But you won’t erase it from your memory: this silent prelude colors the entire day. You can’t escape it—unless perhaps you never opened your eyes or raised your head from the pillow. However, you always obey: you open your eyes, and once more you see your room, the books on the shelves, the clothes thrown on the armchair. Involuntarily you ask, who’s chosen the key, why can you play your day in just this way, and not another? Who is that secret demiurge of doom? Do you at least select the melody yourself, or have They already shackled your thoughts?

It’s of enormous significance whether the morning’s images are just a tangle of memories, merely faded pictures of locations, faces, or incidents you’ve seen before, or if they appear within you for the first time. Memories color life in more or less familiar colors, while a day that begins with nonexistent sights is dangerous. On days like that abysses open up and beasts escape from their cages. On days like that the lightest things weigh more than the heaviest, and compasses show directions for which there are no names. Days like that are always unexpected—like today (if that was today) . . . An old house in the depths of a garden, an elongated woman’s face, a break in a solid wall of blind windows . . . I immediately recognized Karoliniškės’s cramped buildings and the empty street; I recognized the yard where even children walk alone, play alone. I wasn’t surprised by the face, either, her face—the frightened, elongated face of a madonna, the eyes that did not look at me, but solely into her own inner being. Only the old wooden house with walls blackened by rain and the yellow leaves scattered by a yellow wind made me uneasy. A house like a warning, a caution whispered by hidden lips. The dream made me uneasy too: it was absolutely full of birds. They beat the snowy white drifts with their wings, raising a frosty, brilliant dust, the dust of moonlight.

How many birds can fit into one dream?

They were everywhere: the world was overflowing with the soundless fluttering of delicate wings, sentences whispered by faces without lips, and a sultry yellow wind. The dream hovered inside and out, it didn’t retreat even when I went outside, although the yard was trampled and empty, and parched dirt covered the ground in a hard crust. It seemed some large, slovenly animal had rolled around there during the night. A scaly, stinking dragon scorching the earth and the asphalt with its breath of flames. Only it could have devoured the birds: they had vanished completely. There wasn’t a single bird in the courtyards between the buildings. The dirty pigeons of Vilnius didn’t jostle at their feeding spots outside the windows of doddering old women. Ruffled sparrows didn’t hop around the balconies. There wasn’t a single bird left anywhere. It seemed someone had erased them all from the world with a large, gray eraser.

People went on their way: no one was looking around with a stunned face, the way I was. They didn’t see anything. I was the only one to miss the birds. Perhaps they shouldn’t even exist, perhaps there aren’t any in the world at all, and never were? Perhaps I merely dreamed a sick dream, saw something menacing in it, and named it “birds”? And everything I remember or know about birds is no more than a pathological fantasy, a bird paranoia?

These thoughts apparently blunted my attention. Otherwise, I would have immediately spotted that woman with the wrinkled face; I would have sensed her oppressive stare. I consider myself sufficiently experienced. Unfortunately . . . I walked down the path that had been trampled in the grass, glanced at the green stoplight, and boldly stepped forward.

Instinct and a quick reaction saved me. The side of the black limousine cleaved the air a hair’s breadth away from my body. Only then did I realize my feet weren’t touching the ground, that I was hanging in the air, my arms outstretched. Like a bird’s wings.

My body saved me. I jumped back instinctively; I won against the car fender by a fraction of a second. My heart gave a sharp pang; I quickly looked around and spotted that woman. Her wrinkled face yawned like a hole against the background of the trampled field. Her stare was caustic and crushing. She gave herself away: none of the people at the trolleybus stop were standing still; they looked around, or glanced at their watches. She stood upright, as motionless as a statue, and only her cheeks and lips moved—you couldn’t mistake that motion, like sucking, for anything else. I also had time to notice that her gray overcoat was frayed (severely frayed). Without a doubt, an ordinary peon of Theirs, a nameless disa. She suddenly shook herself as if she were breaking out of shackles and nimbly leapt into a departing trolleybus. There wasn’t any point in following her (there’s never any point).

I glanced at her for a second perhaps—the black limousine was still quite close. As if nothing had happened, quietly humming, the limousine sailed over the ground. The back window was covered with a small, pale green curtain. They really had no need to cover themselves. I knew perfectly well what I would see if the little curtain weren’t there: two or three pudgy faces looking at me with completely expressionless, bulging eyes.

The birds came back to life only when I got to the library. Two dazed pigeons perched by the announcement post. They practically ignored the passersby, merely rolling their deranged eyes from time to time, without moving their heads. They could neither fly nor walk. Perched on three-toed feet, they listlessly bulged from the grayish cement, as if they were in a trance. The ancient Sovereign of Birds had forsaken them.

O ancient sovereign of winged things, shepherdess of a thousand flocks, give all those hiding in the thickets to me, throw a skein of wool before the man who is searching, tracking the footprints; lead us forward in the eye of day and in the light of the moon, show the way no human knows!

She waited for me in the library corridor. I say “me,” because sometimes it seems that everything in the world happens for me. The grimy rains fall for me, in the evening the yellowish window lights glimmer for me, the leaden clouds contort above my head

. It’s as if I’m walking on a soft membrane that sinks under my feet and turns into a funnel with steep sides; I stand at the bottom, and all incidents, images, and words tumble down towards me. They keep sticking to me, each one urging its particular significance. Perhaps only a presumed significance. Although, on second thought, everything could be immeasurably significant. I have found her leaning on the window many times before. She’s probably not waiting for me; maybe she’s waiting for her own Godot, a tiny, graceful Nothing. I know how to distinguish those who wait. She always stands by the window waiting and smokes, the cigarette squeezed between her slender, nervous fingers. Perhaps her Godot is the grayish-blue sun—the color of cigarette smoke—shining outside the window. Or maybe I am her Godot after all, stuck at the bottom of the slick-sided funnel, beset by dreamed-up birds vanishing and appearing again and beating the dusty twilight of the library’s corridors with their wings.

She rocks back and forth almost imperceptibly, a slightly bent leg set in front. It seems she intentionally intoxicates with the hidden curve of her long thighs. They’re not particularly hidden: no clothing can cover her body. I don’t understand her, or perhaps I want her to remain mysterious as long as possible. I don’t turn my eyes away from her; even if I wanted to hide myself, she would force herself on me anyway, through hearing, touch, through the sixth or seventh sense. What is she—fate, or a treacherous snare? She doesn’t force herself on anyone, she simply exists, but incidents, images, and words constantly slide down the funnel’s slopes, closer to me each time. I avoid her a bit, maybe I’m even afraid. I can’t stand it when some person turns up excessively close.

We worked together for two or three years and it meant nothing to me. I scarcely noticed her. And suddenly, one miraculous moment, my eyes were opened. Since that moment she’s all I see.

She’s unattainable; she doesn’t pay the least attention to me. Why should she? I’m old, she’s young. I’m hideous, she’s beautiful. She could at least stop irritating me and distracting me by her mere existence. I know my destiny; I’m not reaching for the stars in heaven.

When was this; when did I think this—surely not today?

She sensed me, turned and showed her eyes (probably brown), wandering in from that morning’s vision. She doesn’t look at me; that brown gaze is always turned towards her own inner being, there, where the drab sun’s rays do not reach. Inside, she is teeming with hidden eyes, while the two eyes that are visible to everyone are merely two lights, two openings breached by the world squeezing its way into her unapproachable soul. Soul, spirit, ego, id . . .

But when, when was this, when did I think this way?

I slipped into my room and quickly closed the door. I closed the door, pulled the curtains shut, and unplugged the telephone. I know perfectly well what I’m hiding from. Particularly today . . . Although what does “today” mean? What does “yesterday,” “a week ago,” “a month from now” mean? What does “was,” “will be,” or “could be” mean? I grasp the world far more essentially, without the deceptive entanglement of time. I was first taught the secret art of understanding in dreams and visions, and then here, in the world we feel with our fingers. I pay less and less attention to humanity’s banal time; it’s too deceptive, it leads you astray from the essence that hides in one great ALL. I can’t allow myself to be deceived by thinking that something has “already passed by,” or that something else is still “to come.” Thinking that way destroys the great ALL’s unity. Now I sit at my desk in the library’s office and painstakingly lay out stiff paper cards. Now I stand entirely naked in front of the mirror. Now I plunge into the dizzying black-eyed Circe’s body. Now I fearfully step into the old house in the depths of a garden . . . I stepped into, I will step into, I could step into . . . All of that happens at the same time in the great ALL, those purported differences have no meaning, they aren’t essential. What is essential? That always, every second, slowly and quietly, I molder in one great ALL.

“How old are you, snot-face?” asks the sniffler.

“A hundred!”

“See—the little bastard is still yapping.”

Swinging his arm, he strikes, the brains disintegrate, from the wall the shit-god of all dogs, the mustachioed dog-god sniffs around Georgianly and smiles.

“Now, how old are you?”

“Six hundred twenty-three!”

The morning’s events weren’t, of course, accidental. I’d like to not pay attention to anything, to say to myself that it was accidental, that there was nothing to it at all. I’d like to forget the wrinkled woman’s oppressive stare, the pigeons by the announcement post, and the murderous black limousine’s fender. But I don’t believe in accidents. They don’t exist. Everything that happens in life is determined by you yourself. All “accidental” failures, all misfortunes, all joys and catastrophes are born of ourselves. Every fiasco is an unconscious fulfillment of our desires, a secret victory. Every death is a suicide. As long as you cling to the world, as long as you don’t surrender, no force can overcome you. Everything, absolutely everything depends on you yourself; even Their tentacles don’t reach as deep as They would want.

I’ve summoned Them again; once more I’ve given myself away, I’ve attracted attention. There can be no doubt: the shabby disa’s stare, the unmistakable movements of her lips and cheeks were excessively clear . . . The horror is to know that it’s as inevitable as the grass greening up in the spring, as the dragon’s fiery breath. For a little while They stopped hiding and took aim at me again. My life is the life of a man in a telescopic sight. There would be nothing to it if the shotgun that is aimed at me would merely kill me. Alas . . . Who can understand this horrible condition, a condition I’m already accustomed to? Who can measure the depth of the drab abyss? The worst of it is that the trigger of that unseen shotgun is directly connected to you. Only you can pull it, so you have to be on your guard every moment, even when you are alone. Perhaps the most on guard when you’re alone. Mere thoughts and desires, mere dreams, can give you away. They watch you, they watch you all the time and wait for you to make a mistake. With the second, true sight, I see the crooked smirk on Their plump faces, a smirk of faith in Their own unlimited power. But I barely try to inspect the mechanism of Their actions when I run into a blank wall. It’s easy to get into Buddha’s world; hard to get into Satan’s.

God’s world, Satan’s world, the worlds of spirit, pain, fear . . . But there is an ordinary world too, the real world; you always return to it, you’ll never escape it—just as you’ll never escape from Them. It counts its absurd time, never missing so much as a second. Now its clock says it’s noon. Two hours have disappeared, devoured by silent jaws. My time frequently disappears that way. You’d think you’ve fallen into a deep pit of time; all that can be seen from there is a pathetic little sky-blue patch of time that’s always the same. And the insane clocks of the empirical world don’t stop going; death hides in their ticking. Thank God, I fall into the pit and calm down there. Sometimes I envy myself this ability. It’s like sleep without dreams. In the forced labor camp I would walk and talk for entire days (now I walk and talk), but in fact I would be on the other side of the barbed wire fence, on the other side of all fences, on the other side of my own self. Later I wouldn’t remember either my words or my actions; that may be the only reason why I survived all the horrors. Unfortunately, from any sleep there is an awakening. It falls to your lot to return here.

Strange—even here I’m appropriate, allowed, possible. That’s practically a miracle. I should have long since flown out of this world to end up in God’s, Satan’s, or fear’s universe. However, for the time being I’m still here. I even almost have friends.

It’s probably all right now to pull back the curtains, to crack open the window—and immediately Stefa, without knocking, sticks her head in through the door. She invites everyone to take a coffee break: a charming little head with white-blond hair and sparkling eyes, hurrying to see everything she shouldn’t.<

br />

“Toast his pecker a bit,” says sniffitysniffler.

The portrait on the wall twitches its mustache like mad.

I follow behind her, down a low, straight corridor. Slowly I turn into the ordinary outward “I”; soon he will quietly sip coffee. Brezhnev’s portrait hangs at the end of the corridor; Stefa’s wide hips sway in front of me rapaciously. It’s almost a scene from childhood: Robertėlis sits under a portrait of Vytautas the Great while Madam Giedraitienė, even in front of me, a teenager, sways her hips erotically.

Unfortunately, the portraits differ too much. Bloated Leodead Brezhnev, with grinning, artificial jaws. Even his brains are artificial. More and more like Mao’s last pictures. In the end they all become as similar as twins—there’s some secret hiding here. They’re artificial, put together out of non-working parts; when they speak, barely grunting out the words, it seems they are going to disintegrate any minute. And yet they don’t disintegrate. They’re the live apotheosis of kanukism; They give themselves away, propping up stooges like that.

No, no, better Robertas under Vytautas’s portrait. Later he sits down to play a minuet while I stare at Madam Giedraitienė’s seductive hips, Stefa’s hips, all the hips of all the world’s women; they dive into the opening of a door, Virgilishly and slavishly lead to an apple cake and a circle of hell made up of plump, feminine faces.

Because above the table, shit on the beans, hangs the portrait of the mustachioed man, the rightlower corner cracked, the mustachioed man’s a bit battered. Stalin Sralin,1 baby swallower. But we won’t be afraid of him; we’ll shove a rod up his ass.

Shit on peas, shit on beans,

Shit on Stalin’s flunkeys . . .

Vilnius Poker

Vilnius Poker