- Home

- Ricardas Gavelis

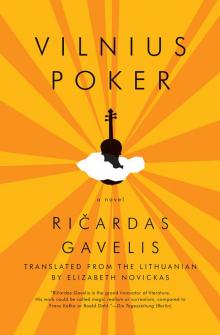

Vilnius Poker Page 14

Vilnius Poker Read online

Page 14

I sensed that the catastrophe couldn’t hide only inside her. I knew I had to investigate what she did outside of the house, whom she met with and where she went. I had already caught on to a few things, but I still couldn’t entirely grasp what path I was taking, my thrashing heart squeezed into a fist.

She didn’t sense she was being followed (I had opportunities to convince myself of this), but she always escaped from me. This stunned me: even without sensing the real danger, she maintained an absolute conspiracy. She would disappear through courtyard passageways, or simply turn a corner and vanish, as if she had floated off into the air. I would search for at least a door, a window, a crack in the wall where she could have disappeared. Unfortunately, always unsuccessfully. She was attracted, drawn into the old part of Vilnius, closer to the narrow little streets and churches, the neglected buildings and gloomy, filthy courtyards. You’d think it was only in Old Town that she could disappear, in league with the spirit of Vilnius itself. That spirit of the city intimidated me. All of Vilnius grew faint and muffled, all there was left of it was crooked, fly-stained little streets and dirty courtyards with whitewashed toilet stalls. The city shrank into the narrow, decrepit buildings, into the realm of the ground-floor dives. In the courtyard passageways I would be met by bandy-legged dogs and dirty chickens. The entire motley pack would furiously sniff me over. Dazed men staggered along the walls. Shrill women hung laundry on sooty clotheslines. In the squares, sullen groups guzzled the cheapest garbage wine out of bottles. Hoarse, drunken cries bounced between the thick walls; I practically didn’t hear a word of Lithuanian anywhere. It seemed I was no longer in Lithuania, that at any minute I was going to have to speak a narrow gutter language I didn’t know. My ancient, sacred city was beset by the lowest order of lumpen. I had to shove my way through them to follow the waddling woman’s figure. She felt at home between the fly-stained walls, even her walk would improve. But I was an alien here, and not welcome. Bleary-eyed men looked at me with surprise and a strange malice. Surprised dogs would sniff at me, unable to understand what that smell was doing here. I was shocked: it had been many years since I had seen this Vilnius. But after all, my own old spirit had to linger here; I myself, as I was ten or fifteen years ago. Perhaps she was intentionally attempting to lure me back to the past.

There was no peace left at home, either. Increasingly weird characters began visiting, as if bugs had converged on my apartment from unknown cracks and corners. They beset my house like apparitions. They were seemingly different, even very different, but at the same time exactly the same as her. My practiced eye already distinguished the critical details: the unusual movements, the emptiness of the gaze. All of their hands were chubby, with swollen joints, and covered in small, tawny freckles. From every one emanated the familiar sour smell of decay. One sturdy fellow, by the name of Justinas, seemed especially typical to me. (He was some sort of party functionary, a representative of the nomenklatura, a person from a special world where everything is different than it is in our life: things, and food, and hospitals. Even bread is baked specially for them. Even the rules of the road are different for their cars.) I kept trying to talk to him, even though I didn’t know what I needed to question him about. I simply tried to earn his confidence, to encourage him to chat freely. I would fix the coffee and make toast myself, leaving Justinas in the room with her. I would secretly listen to what the two of them talked about. But he didn’t give himself away: not a word about Old Town, the Narutis neighborhood, or the courtyard passageways.

Justinas immediately made himself completely at home; it seemed entirely natural to hug my wife in a friendly (or not just friendly) way, or to pat her on the knee. Once, when I had stayed a bit longer in the kitchen and returned quietly, I caught him pressing her breasts in his hands. We were all a bit drunk. I pretended I hadn’t noticed, but before going to bed I threw a jealous fit. I was stunned by her reaction. Suddenly she got really nasty and launched into an attack. I was the one who was to blame. I had invited Justinas over. I had created an unhealthy atmosphere. I alone. I listened to her croaking voice, looked at the pimply face, the deformed fingers, the bloated breasts, the globs of flesh between her thighs, which she hid under a thick nightgown but weren’t difficult to infer; I looked and I couldn’t help but be charmed. This time she played the part perfectly. She smeared her face all over with mascara, writhed like a snake, and heaved in the most disgusting convulsions of kanukism. She truly had not lost the talents with which she had deceived me our entire life together.

She didn’t lose her ability to disappear, either. It seemed I should have given up my useless stalking long ago, but my determination never knew any limits. Determination sooner or later pays off. One time, as usual, I lost sight of her and aimlessly went in circles around the neighborhood of the Narutis; finally I went out into Didžiosios Street, stopped, and lit up a smoke. Apparently, the tension was already accumulating within me; the second sight was already emerging. I sensed that I had to look to the right; I sensed this command coming from within. First I saw her; then that creature too. She slowly crept towards him; without turning his head he muttered something to her and continued to stand there, as if he were rooted to the spot. She hunched over even more, and, obediently, as if she had received a blessing, hobbled off. She no longer concerned me; I fixed my eyes only on him. He was stocky and square. He stood by the wall next to the door of a store. Next to the scurrying, rushing figures he looked like a hole in a colorless carpet. He had no neck at all. His massive head was set directly onto his shoulders; if he wanted to look to the side, he had to turn his entire body. But he didn’t turn; he merely devoured everything with his eyes. That neckless thing had grown into the paving stones, into the grim walls, into Old Town’s close air. Passersby would slow when they passed him; it seemed they forgot for a moment where they were going. But this didn’t interest him; he simply stood there and devoured everything with his eyes. He riveted my attention, riveted even my willpower. The eyes in his pudgy, flat face were like two holes—if it’s possible to imagine holes in a hole. His face was completely expressionless, but it was just this lack of expression that broadcast his oppressive menace, his universal scorn, and his firm belief that this was his domain. Superficially, he looked like an imbecile, but I didn’t doubt for a second that inside him an iron, dispassionate intellect was working like a machine. His head jutted out of his shoulders and was bent somewhat forward; he seemingly charged forward, but at the same time remained as unmovable as a rock. He was like a wolf poised just before a leap, but firm in the knowledge that it would be unnecessary to pounce—the victim would climb into his jaws on its own. A pathological threat, indescribable in words, was hidden inside him. It was only possible to feel it; it penetrated my innards like a plague bacilli, like a sense of impending doom. At intervals, faceless figures would approach him for a blessing; he would growl something, and they would slink off again. I saw he was the secret king here, whom everyone obeyed without knowing whom they were obeying, and naïvely thought that they were acting independently. He held all the strings in his hands (whose strings, what strings?); he loomed above Old Town like a gigantic octopus, connected by innumerable threads to the mass of drab figures who were crawling here and there. His proboscises reached everywhere; they reached my innards too—my chest was encompassed by a torpid weakness. I felt I had already found it, but I still couldn’t understand what I had found. I was alone—frightened and helpless. I was and I remained alone.

Now I understand how lucky I was. I never again succeeded in seeing one of Their commissars, a high overlord, so close up—simply in the street, in the crush of passersby, for some reason breaking the codes of secrecy. I don’t know what I would do now, but at that time I simply froze, gasping for air with my mouth open, feeling nothing but a boundless fear and a pain in my chest. That creature stirred and slunk off along the wall, but I couldn’t budge: I was paralyzed. I had come across Their outpost, but I wasn’t prepared; I didn’t h

ave sufficient strength to risk it. Apparently, They had undermined me too; the tree of my spirit was not exactly flourishing. However, there was still sap there, even though They believed they had already dealt with me. It wasn’t true—I was still alive. It was just that the time hadn’t come yet. Only a person who is focused and resolved to sacrifice himself can begin to do battle with Them. A person who has no other out.

. . . and everyone’s lounging about as if they were at a health resort. It’s some kind of communist holiday today; for breakfast you each got a genuine roll with marmalade. You’re sitting in your nook by the garbage cans again. A couple of Russkies rummage through the refuse—today no one will yell, no one will assign you to solitary, no one will knock your teeth out. Bolius is terribly emaciated; even here it’s rare to see such a tortured face: a desiccated, sapped, disfigured face. But it’s a human face regardless. No blind strength, no hatred can wipe off the marks of a great intellect, the marks of a great heart; nothing can extinguish his eyes. You’re actually intimidated. The man who is probably the greatest intellect of Lithuania, the honorary doctor of a hundred universities, the intellect of Lithuania’s honor, is sitting next to you, talking to you and teaching you, Vytautas Vargalys, as if you alone were all of poor strangled Lithuania, waiting for his word.

“After the war the Russians took land, technology, and gold away from Germany, but they never managed to appropriate German Ordnung,” Bolius lectures. “In a German camp, the sadism is precise and refined; here the sadism is primitive and brutish. Russia is still Russia—even in a camp . . .”

“You were in Russia before the war?”

“No, this is my first time here. They brought us here by train straight from Auschwitz—without switching trains, without any visas. Like in a relay race—straight from Hitler to Stalin. Not just me—all of us—millions . . .”

“Why?” You ask involuntarily. “In the name of what?”

“Why me?” Bolius rephrases the question, his eyes gleam with a strange sarcasm, “You? All of us? Because we’re breathing. Because we’re alive. Lithuania without Lithuanians! You know, after all, that’s the Soviet leaders’ slogan. You know that.”

“Then why the Russians?”

“Oh, they’re just along for the ride.” Bolius grins, his crooked smile is awful. “It’s nothing, they’re used to it. It’s worse for us, because we’ve already gotten a whiff of freedom and will never be able to forget it. Blessed are the ignorant . . . The Russians never experienced freedom, so they can’t even dream about it. Blessed are the . . .” Bolius’ voice unexpectedly trembles. “In Auschwitz I used to secretly give lectures: about art . . . about literature, philosophy . . . Dozens of people risked their lives for those lectures . . . They had to feel human, they couldn’t do otherwise . . . But these do without it quite nicely . . . They don’t need it, do you understand?”

You’re sorry for the Russians, who have never tasted freedom, who need nothing. There now, a couple of them are rummaging through the refuse, they’re happy to find a bite. Don’t tell me man was created for this, to rummage through a camp’s refuse, and then for weeks upon weeks, years upon years, to chisel out Stalin’s portrait, as big as an entire village, on the rocky slope of a mountain? You no longer know what a human is. Perhaps Vasia Jebachik is a human? He’s next to you, he’s adjusting his still, but he won’t make moonshine—it’s a tea brewer. Vasia Jebachik is the ruler of this world. Bolius looks at you, and he sees right through you.

“You think I’m not sorry for them?” he says. “You think I’m not driven to despair that I can’t do anything? . . . Look around: this is what their world is. The sun shines, so they’re all happy. They each got a roll, so they’re all satisfied . . . They have no doubt that things are the way they should be . . . The doubting ones are long since under the ground . . . Still others console themselves with the thought that it’s an unfortunate mistake, but shortly a bright future will arrive . . .”

Bolius closes his eyes; he doesn’t want to show the suffering in them. He wants you to see only wisdom in his eyes, a clever Voltaire-like little smile, so that at least in your thoughts you’d forget your desecrated body and believe that the spirit can’t be fenced in with barbed wire.

“They’ll do the same thing to us,” you say suddenly. “We’ll be praying to the Shit of Shits too.”

Bolius opens his eyes in a flash, you actually recoil—the anger that flows from his gentle eyes is so unexpected.

“Son!” he spits out fiercely between clenched teeth, “You don’t know what a human is. Listen carefully: HUMAN! It’s impossible to defeat a human. You can kill him, but defeat him—never. They’ve taken everything away from me: my wife, children, freedom, love, the world, God, learning, the sun, air, hope, my body, they’ve done everything so that I would no longer be myself, but they haven’t overcome me. And they won’t! Within me lies an immortal soul, whose existence they deny!”

Bolius roars, even Vasia Jebachik lifts his eyes from his still and glares sullenly at the two of you.

“Ironsides, shut your prof up,” he says sarcastically, “He’d better be quiet. The Doc keeps staring at him, and if he takes him to the fifth block—none of his gods will help him. Neither Buddha, nor Shiva, nor that little Jew Einstein.”

Justinas was like a splinter driven into my life: I stumbled over him wherever I turned. He acted friendly with me, but somewhat from above: after all, he belonged to the cream of the party, and I was nothing more than a computer specialist. I no longer listened to what he was saying; I sensed he wouldn’t give himself away with words. I studied only his face and hands. I would look at the double roll that was forming under his chin, at his soft, indistinct features. His face was covered with a thin, barely noticeable layer of fat, but it wasn’t just an ordinary layer of fat, the result of pointless gluttony. That layer—puttied over the sharp corners, protrusions, and hollows—was a natural part of his construction. Justinas’s face couldn’t express sudden or strong emotions, that’s not what it was made for. It was designed for something like emotions, for half-feelings and a calm, stable existence. His eyes were the color of water. His hands, however, held the most meaning. A strange, unfathomable hieroglyph hid inside them. A hieroglyph of decay, stagnant water and twilight. They were pale and covered in brown freckles, with swollen joints. The fingers were stumpy, bloodless, and almost transparent. There were no veins to be seen on his hands. Those hands wouldn’t leave me alone. An irresistible desire kept coming over me: to cut into Justinas’s finger and see what would run out of the wound, what there was inside of him. Probably a continuous gray mass, a sticky bog of non-thoughts and non-feelings.

He got along famously with my wife—their thoughts and words, and even their movements, coincided. The two of them looked like brother and sister. I felt I was standing on the threshold of the secret. Sometimes I got the urge to track Justinas, and sometimes I unexpectedly felt sorry for her, or more accurately, for the pathetic remains of my Irena that would at intervals flare up in her. A human is weak: I would caress her secretly in the dark of the night, examine the body, lost in dreams, with the tips of my fingers. A human’s sensations are deceptive: sometimes it seemed that I didn’t feel the triple rolls under her breasts, I didn’t find the disgusting globs of flesh between her thighs, I didn’t feel the coarse hair tangled around her nipples. I was completely deranged: sometimes I talked to her, sometimes to my Irena. I had to resolve to do something, but I didn’t know what. I kept trying to lure her out into the yard when I heard Jake barking. I wanted to bring the two of them eye to eye, and see either bristling hair on the nape, insane eyes, and bared fangs, or a tail wagging hysterically and a tongue trying to lick. But as soon as Jake’s yelping sounded, she would find piles of work that couldn’t be put off. The longer I failed to bring the two of them together, the more I believed the dog would decide everything. Sooner or later the two of them had to meet, and then . . . “Then” came one gloomy Saturday morning. She was bore

d and, of her own accord, suggested we go outside. I was about to argue against it; I wanted to read, but I glanced out the window and saw Jake romping around the yard. I went down the stairs with a numb heart; I almost wanted to grab her by the hand and drag her back home. I secretly hoped Jake would have run off somewhere.

But Jake was lying next to the bench, all tensed up, ready to jump up and bound towards us. She turned to him first, squatted carefully, stretched out her hand and, crying out, jumped back. A bitter smell of mold suddenly spread through the yard. My leaden feet wouldn’t carry me closer, I didn’t want to know anything, and for a few long moments I didn’t know anything, but suddenly, almost against my will, I understood it all. It would have been better not to. The dog was dead. His infinitely lifelike pose, his open eyes gazing forward, completely did me in. An instant before he was energetically romping about, even now his doggy soul hadn’t yet entirely left his body, but at the same time he was somehow especially, hopelessly dead. She wailed out loud, caressed the rigid, curly-haired body, and I dare say even forced out a tear. I didn’t believe a single one of her wails, not a single one of her movements. That time she played her role badly, no one in the world would have believed her. The yard immediately got sickeningly colorless; the smell of mold or decay became unbearable. I was seriously frightened; I was afraid to even get close to her. The cowardly, nervous little person deep inside my soul just wanted to run, to escape as far as possible, to dig under the ground, to crawl into a cave and tremble there. The other—the brutal man who had gone through hell—wanted to strangle her with his bare hands. I wanted to howl, when suddenly she turned around and looked at me with Irena’s pure, sad eyes.

Vilnius Poker

Vilnius Poker